By Matt George, a freak of a human: Former professional surfer, adventurer, screenwriter, journalist and contributor, to pretty much every surf magazine you could think of.

„He worked as a Karl Lagerfeld model, attempted to become a Navy SEAL, fought in Golden Gloves boxing tournaments, holds a calf roping record in Hawaii, has raced Sumbawan Water Buffalo and twice climbed Mount Kilimanjaro. He was a first-responder to the 2004 Tsunami, has built remote helicopter pads in Kashmir for the United Nations, has aided in jet-ski rescues after Hurricane Katrina and has been tortured by experts.“ - Magicseaweed

This article was published in our latest Yearbook 2020. Print is best. The printed version is available here.

THE LAST TIGER - Part one:

Silently moving from the jungle, she takes her place on a small rise that looks out over the ocean. She had time yet. The late day sun was cooling and she was waiting for a smell. The scent that came when the ocean would withdraw and the land beneath would become exposed to the sky. Then she could saunter down among the shallow green pools of water and slap fish and crabs and eels from the shallow pools with her great paw. The monkeys would follow her. Cautiously. And they would dart in for a steal as her pile of fish and crabs and eels grew behind her. She would roar at this and swipe at the monkeys and like a flock of birds the monkeys would scatter and reform and try again and again. When it came time to feed she would carry her pile of food in her great jaws and go back to her spot overlooking the reef. There she would hang her head and eat slowly. And she would listen for signs of danger in the silence that came between the great waves that would roll in hissing unison across the edge of the reef in the distance. Later the sun would set and she would return to her mate and cubs and they would hunt the wild boar together until dawn. Suddenly her head shot up, ears pricked, eyes searching. Finding an odd sight. Men. Two men. Pale men. Approaching on foot on the beach. Always a danger, men. Though she sensed these two were weak and tired. And they carried things that did not look like danger. Unlike the steel poles the poachers used. And the two men on the beach were not interested in the jungle. They were always looking out to sea, shading their eyes, again and again. Still, she decided, she would have to keep her distance until she knew more about them. Knew how to eat them. She left the scraps of her food for the monkeys and, as silent as smoke, vanished into the jungle.

THE DISCOVERY HEARD AROUND THE WORLD

It all started with a volcano.

At over 3000 meters Gunung Agung, an active volcano, lords over the island of Bali. Essential to the Hindu culture of the island, the people believe that each earth day begins when the first rays of the morning sun touch her summit. They call this moment “the morning of the world”. In 1972 a young filmmaker named Alby Falzon debuted a fledgling surf film which featured the first, modern, idyllic images of surfing in Bali. He had borrowed the name of his movie from this Hindu summit belief, naming his movie “Morning of the Earth” instead. And from the moment it flickered on screen in Australia, surfing in Indonesia would never be the same.

Surfers flocked to Bali in droves to surf her absolutely perfect waves. Bali was flaming sunsets over golden beaches, postcards of bare-breasted native women, and swirling, impossibly colorful dance troops. Fully booked airlines landing on runway 270 afforded a dream view out the starboard windows of the five best waves on the planet marching down the Bukit peninsula. Surfers would deliberately book their seats on this side of the aircraft just for the chance to glimpse this phantasmic sight. Bali was exotic, friendly, and cheap. Everything from beach huts to beer was always near at hand for the budget surfer. Why, oh why, look any further for paradise.

Yet is was inevitable that this global surfing pilgrimage would eventually interrupt the idyll. And as the crowds grew and grew, a few minds turned to the possibility of new discoveries. After all, Indonesia was a country of 17,500 islands.

THE TRUST FUND KID

From the beach at Kuta on Bali, on a clear day, you can just see the south east tip of Java. Shrouded in mystery like her name itself, Java was talked about in hushed tones by most. A land of hardcore third world poverty, Government coup attempts, student riots, bloody communist purges and a stone-faced dictator in cop shades and military dress.

Enter Bob Laverty in 1972, a young trust-funded surfer from Southern California who was searching for himself in the far reaches of the orient. On a local flight from Jakarta to Bali, the weather diverted his flight and Laverty found himself flying over that very same tip of Java that he had wondered about when looking on from Kuta Beach. He now was directly over the Plengkung jungle, a lonely, expansive, dried out national reserve. Laverty was looking down upon row after row of crescent swept whitewater lines that formed a perfect phalanx as they moved down from the top of the point into an enormous azure bay. The fire was lit.

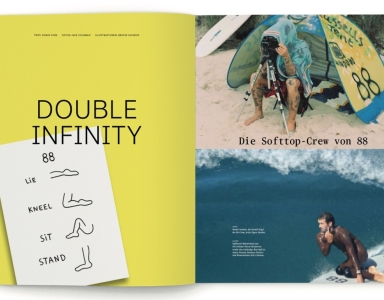

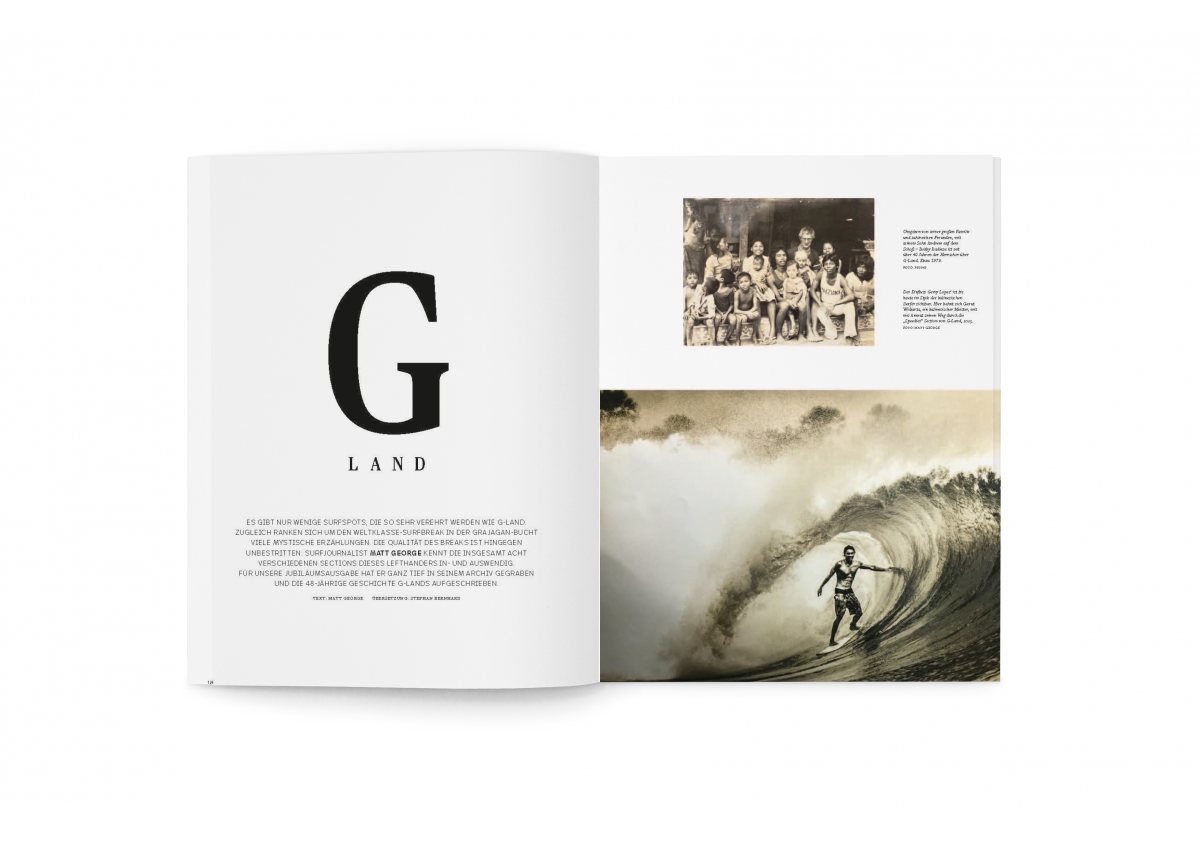

This view was witnessed by Bob Laverty in 1972, when looked outside his window as his plane had to fly a detour caused by a storm. Grajagan: The prototype of any surf camp and resort and the foundation of a multi-million dollar industry. Photo: Dick Hoole

Back in Bali Laverty got to work. He got his hands on a British Admiralty Chart of Java and located the bay. Next he needed partners in crime. Bali surfer expats Bill and Mike Boyum were the best candidates. Laverty unrolled the map where his “x” marked the spot. A mere 67 miles from where they stood in their Kuta beach bungalow. Hire a boat? Too risky and unpredictable with no knowledge of anchorages and wild seas. It would have to be overland. Even though that prospect was horrendously dangerous. Mike passed on the whole adventure. But Bill was bitten by Laverty’s bug. A partnership between Bill and Laverty was formed.

Laverty and Bill Boyum left at dawn on rented motorcycles packed with supplies and surfboards slung on straps over their shoulders. Then it was a sketchy voyage across the strait into the open Indian Ocean and then to a small fishing village. The chart named the small port Grajagan and it hugged the very opposite end from where they wanted to be in the great bay. Arriving at the port of Grajagan, they entered a very different world. Filled with all the dazzlement of the Muslim culture. Just as the mid-afternoon muezzin call to prayer was crying out from the mosque, Laverty and Boyum pushed their bikes onto a dugout fishing boat and pointed to the far end of the bay. The captain of the dugout took them as far as he dared. The jungle of the Alas Purwo National Reserve was a place of great superstitions. A no man’s land filled with tales of black magic, spirits, snakes and bloodthirsty tigers. The Captain dumped them a good ten miles from the top of the bay and got the hell out of there, leaving them and their bikes on a jungle-edged beachfront. The hard-packed low tide sand was okay for the bikes and they pressed on, their lust for surf making them all warning signs. At one point a large flock of Flamingo’s was startled by there bikes, a species that was not even known to be in Java. Then the sand, and their luck, if you could call it that, ran out.

It was now late afternoon. They abandoned the bikes to the jungle and were now afoot. They could see the offshore spray coming off the waves, probably four miles distant. It was slow going as the tide crept in and pushed them closer to the Jungle. As the sun went down, they hadn’t even covered half the distance. With no choice but to press on by a sliver of moonlight, they groped along until they could hear the regular sound of the surf. They then feel exhausted on the beach and slept. At one point in the night they were awoken by the roar of a Javanese Tiger. Neither of them had ever heard such a spine-chilling sound in their lives. They then slept in shifts with sharpened spears fashioned from driftwood.

Boyum and Laverty woke to a blistering sunrise, sandy and sore, and looked out to sea. As the first set of waves marched in, they stood in awestruck silence, knowing that they had found what every surfer could only dream of. Absolutely perfect, empty 2.5-meter waves, more dramatic and evenly formed than even the great Uluwatu, and without even a hint of another surfer for miles and miles. It was all theirs. There were no Uluwatu cliffs here, no sea snake caves to negotiate, no difficult entry or exit from the surf. An inviting crescent shaped white sand beach gave way to an easy paddle out into an empty line-up. It was by all descriptions an ideal fantasy set-up. Laverty and Boyum, re-energized prepared to paddled out. This is when they noticed the fresh paw prints of a large Javanese Tiger within 10 feet of their small beach camp. “That was a sobering sight”, said Boyum, “And that was where the original idea for the tree houses came in”. They then paddled out and surfed undisturbed for three days until they ran out of water. In the tradition of the first surfers to ride a new spot being allowed to name it, they dubbed their discovery “G-Land”. Even though the break was actually a long way from Grajagan on a point of land known locally as Plengkung.

Big, long and fast boards were dominating at G-Land. The perfect composition of the wave, was the reason for the on going production of Big Wave Guns around the world. The rides were so long, that the surfer often took water and food to the line-up, such as sun glasses for the long paddle out back to the peak. Photo: Dick Hoole

Back in Bali they received a hero’s welcome from a very exclusive group of surfers. Yes, it was a mad adventure. Under constant threat of Malaria, reef cut infections, road accidents, heatstroke, boat disasters, storms and tigers. But undeterred, Laverty and Boyum were already drawing up new plans for a return visit. Tragically, it never happened for Bob Laverty. On the eve of their new departure Laverty suffered an epileptic seizure while surfing Uluwatu and was drowned in large surf.

Yet, the new era of Grajagan surfing had begun. And in many ways the second journey was even crazier than the first. Because the forward thinking Boyum brothers were determined to own and monetize the break for themselves before the inevitable mobs would descend upon it. The concept of the surf camp was born. But at first, they wanted it to be a floating camp. So, the Boyum brothers borrowed enough money to buy a used 24-foot Radon fishing boat, which could get them from Kuta Beach to G-Land in just over four hours on a good day. On a bad day? They would probably die. They thought of this little boat as the concept for a floating surf camp, but lack of room and the outrageous dangers this presented sunk those ambitions. This was when Bill Boyum re-worked his tree house idea. Relegating the Radon to a supply and guest delivery vessel.

Mike Boyum, a drifting gypsy of a surfer, really came into his own at this time and took over operations. A fitness guru, he could play the hippie and fast for days and do yoga for hours, but he could also become a formidable deal maker in a country notorious for its corruption. As stated, the Plengkung jungle was an all but abandoned national forest reserve. But it still meant Boyum’s camp had to be fully permitted. Naturally and some may say fairly, considering that this was not even the Boyum’s birth country, bribes were essential and tricky. Mike Boyum, quickly having become a master at these processes, at one point even removed a family gift gold Rolex from his own wrist and placed it on a certain politico in the name of commerce. With such savvy, within the year, Mike Boyum had obtained the necessary authorizations. In June of 1974, the finishing touches were put on a 15' x 15', thatched-roof, bamboo-sided tree house. Just one. Huge tiger prints were still occasionally seen on the beach, even though the fabled Javan tiger was supposedly extinct. Cobra’s were also a big concern. Searching for firewood could easily end your life. To say nothing of the wild, ivory tusked pigs that could reach the height of a man’s hip. Raising the tree house 20-feet off the ground meant everybody slept a little easier.

Underneath the tree was a kitchen of sorts. Three single-burner stoves, four ice chests, and a 50-pound sack of brown rice. Everything had to be duct taped shut every night, but still the wild animals would turn the kitchen to shambles every night, often gnawing through the duct tape. The surfers got used to the ruckus and could sleep through almost everything except when the tigers came around. They would know when the tigers were around because the jungle would become completely silent.

For the next three years, G-land was the domain of a very exclusive group of surfers. Aside from the Boyum’s there was the great Gerry Lopez, who practically made it his second home, writing gushing features for Surfer magazine from his tree house perch that even included his very personal Haiku poems. Australian Peter “Grubby” McCabe was welcomed. He and Lopez would wile away the hours in the surf weaving and crisscrossing their way down the reef on the same waves. Lopez called it their “Blue Angels act”.

Quiksilver founder Jeff Hakman on a usual day at "Quiksilver Country". G-Land was known under this name, as the surf brand often booked the whole camp for several weeks. Photo: Dick Hoole

By 1977, the camp was government registered as the Blambangan Surfing Club and began taking week-long reservations of ten surfers at a time, $200 a person, with an transportation fee on the beat up boat from Kuta Beach in Bali. From there the price went up quickly. By 1982, a ten-day package cost $1,000.

By this time the famed G-Land had evolved from the world’s finest secret spot to the world’s first surf resort. The G-Land operation could do no wrong and it spiked in popularity. Yet it still held on to its mystique. It was a remote, fantasy adventure wave that called to that adventurous surfer within all surfers. But like all money driven enterprises, the pristine nature of the dream was not to last. Once Boyum's camp proved itself as a solid moneymaker, other surfer-entrepreneurs bribed the right officials, more camps opened, daily boat shuttle services bloomed like mushrooms and soon there were up to a hundred surfers at a time in the line-up.

Lopez finally conceded to every surfer’s lament. “It was the perfect setup there for a few years,” he said, 20 years after his first visit. “It was a surfing monastery. If we could have somehow kept it as such it would have stayed surfing’s Holy Ground…I guess we just shouldn’t have told anybody”.

Despite Lopez’s morose prayer, G-Land still remains a place of mystery and adventure. It is easy to forget that it still lies on the edge of that same abandoned dry jungle, her waves coursing down that same wild point from the top of the bay. A place that will always remind you that you are on the knife’s edge of an exotic, wild piece of the world. Just like the surfers who at 1:17am on June 3rd, 1994 were swept from their G-Land resort beds by the full force maelstrom of a Tsunami. The product of a 7.2 earthquake that rattled teeth lose a full 130kms away. Hitting G-land at 300km an hour, Australian pro-surfers Rob Bain, Simon Law, Richard Marsh, Shane Herring and Richie Lovett were lucky to get away with their lives. It is said that their almost Olympic swimming skills saved them from this watery death.

Quiksilver Pro 1995: Kelly Slater, Damien Hardman, Rizal Tandjung, Mick Campbell, Sunny Garcia and Pat O`Connel. Photo: Dick Hoole

The very next year, in perhaps G-land’s most glamorous period in her long history, was when the Association of Surfing Professionals included G-Land as one of their stops on the global “Dream Tour”....

... to be continued

The full article is available in our Yearbook 2020, available in our BLUE online shop.

//

Credits

Photos: Dick Hoole

Words: Matt George